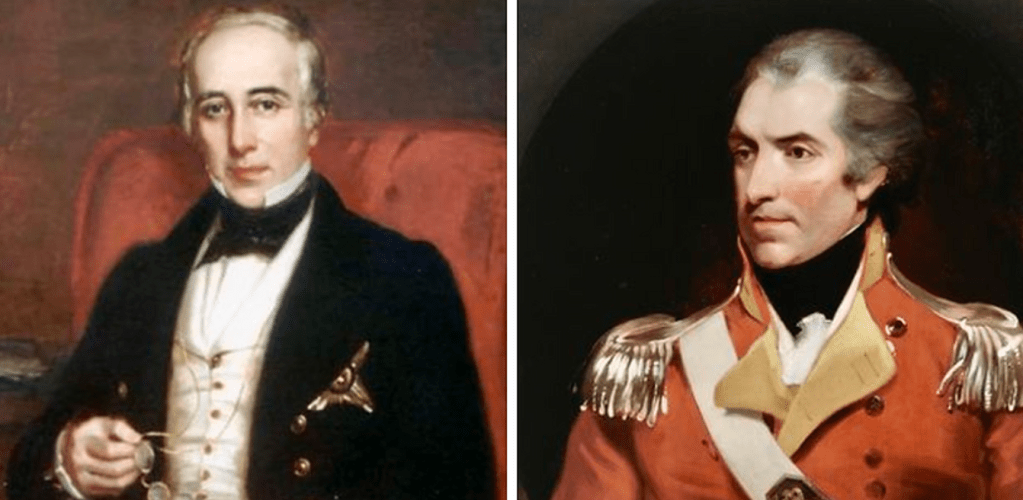

Shortly after Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in May 1824 he ordered the removal of the colony’s northern headquarters from George Town to Launceston.

George Arthur oversaw major changes to the governance of the island penal colony which, after 20 years of British occupation, was still part of New South Wales and administered from Sydney.

He had been told that Van Diemen’s Land, with a population of just over 12,600, of which nearly 6,000 were convicts, was soon to be proclaimed a separate colony, with its own Supreme Court, Executive and Legislative Councils.

The military headquarters for the northern part of the colony was initially established near the mouth of the Tamar estuary by Colonel William Paterson after he arrived in November 1804 but moved to the future site of Launceston in 1806 where there was a more reliable water supply and better farmland.

In 1811, New South Wales Governor Lachlan Macquarie countermanded Paterson’s decision, on military grounds, and ordered the relocation of the headquarters to George Town.

By the 1820s however the agricultural opportunities around Launceston had made it the bigger settlement.

When Lieutenant-Governor Arthur paid an official visit to the north of the island in December 1824, the first issue of the short-lived Tasmanian and Port Dalrymple Advertiser reported his decision to move the headquarters.

The birth of Launceston as the “Northern Capital” was marked by plans for various improvements in the town and an immediate start to the construction of a church (St John’s), commissariat stores (later Paterson Barracks), commandant’s house, parsonage house, hospital and a bridge over the South Esk River, at Perth.

The Port Dalrymple Advertiser published a list of the official names of streets in Launceston, declared “since the arrival of His Honour, Lieutenant-Governor Arthur.”

Brisbane Street, from the Government Cottage, Police Office and Launceston Hotel to the western extremity of the Town; Paterson Street, parallel to Brisbane Street, where the Barracks, Gaol and Government Windmill are located.

Cameron Street, where Cornwall House, the Court House and Naval Office are located; Cimitiere Street, from the Commissariat Stores, past the Tasmanian Printing Office, to the Government Garden, and the Road to Paterson’s Plains [later Elphin Road].

William Street, from George’s Square past Mr Reibey’s; York Street, running parallel to Brisbane Street, behind the Launceston Hotel; Elizabeth Street, parallel to York Street.

Frederick Street, between site for St John’s Church and Capt. Lockyer’s house; Tamar Street, commencing from the punt over the North Esk River, towards Windmill Hill.

George Street, from the Government Wharf, parallel with Tamar Street, and Prisoners’ Barracks; St John’s Street, from the North Esk River, past George’s Square, Lumber-yard, Engineers Office, Launceston Hotel, and site for St John’s Church.

Charles Street, from George’s Square, Commissariat Stores, and the New Road to Hobart Town; Wellington Street, from the Tamar, past the Military Barracks, parallel to Charles Street; Bathurst Street, from the Gaol parallel to Wellington Street.

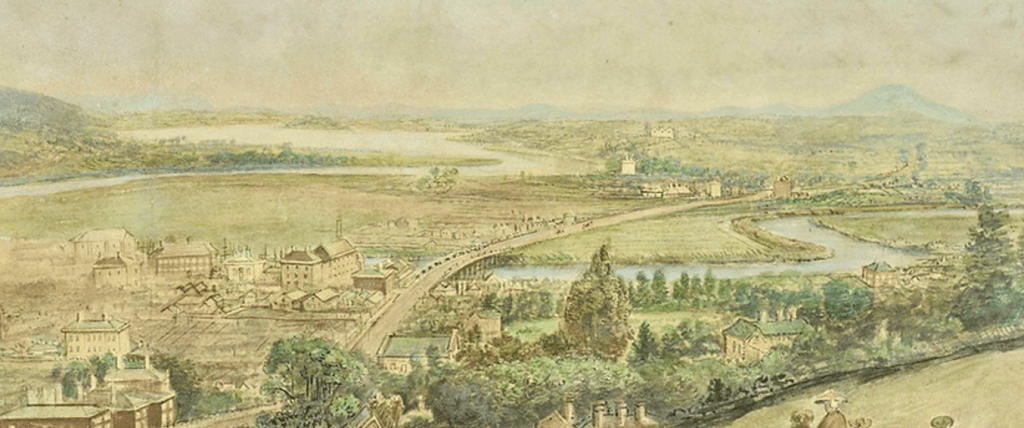

Over the next 30 years Launceston became the thriving commercial and agricultural centre of northern Van Diemen’s Land.

Written for the Launceston Historical Society and published in The Sunday Examiner, 11 February 2024.

Images — TOP: Early Launceston from Windmill Hill c1848, by artist Frederick Strange. QVMAG Collection. MIDDLE: Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur (left) and Colonel William Paterson. BOTTOM: Launceston from Westbury Road c1850s, by artist Frederick Strange. QVMAG Collection.